Introduction

A major open problem in complexity theory involves understanding the relationship between the complexity classes $L$ and $P$. The class $L$ consists of all problems that are solvable by a Turing machine using a number of bits of memory that is logarithmic relative to the size of its input. The class $P$ contains all problems that can be solved in polynomial time on a deterministic Turing machine. It is a well-known fact that $L \subseteq P$, however it is unknown whether the reverse is true: Can any problem that is solvable in polynomial time also be solved in logspace? The Tree Evaluation Problem (TEP), introduced by Cook et al. in [2], is known to be solvable in polynomial time, however it is conjectured to be neither in $L$ nor in $NL$ (the nondeterministic analogue of $L$). To understand the space complexity of the TEP, we study the branching program model of computation, discussed further below. To prove that $L \neq P$, it would suffice to show that any Branching Program (BP) solving the TEP requires at least $\Omega(k^{r(h)})$ states for some unbounded function $r(h)$.

Although the general problem remains unsolved, BP size lower bounds exist for the TEP in a number of restricted models, such as thrifty BPs [2] and read-once BPs [3, 1]. For general BPs, optimal lower bounds exist for the TEP for height-3 trees, and related problems [2]. We hope to extend these results to the TEP for height-4 trees, by studying the problem in various restricted models. If near-optimal lower bounds can be proven for trees of every height, then it would follow that $L \neq P$, resolving the aforementioned major open question in complexity theory.

The Tree Evaluation Problem

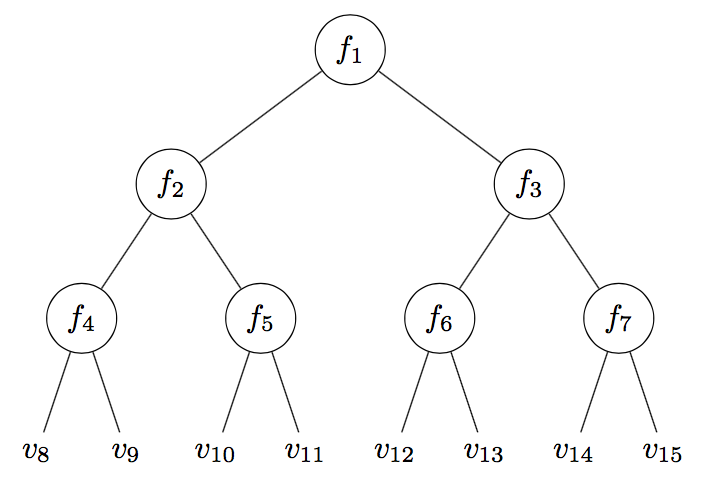

Let $T_d^h$ denote the perfect $d$-ary tree of height $h$. The nodes $v_i$ of $T_d^h$ are numbered in heap style, so that the root node is $v_1$, and when $d = 2$, the left and right children of node $v_i$ are $v_{2i}$ and $v_{2i+1}$, respectively. The tree evaluation problem ${\mathit{FT}}_d^h(k)$ for the tree $T_d^h$ is defined as follows:

Definition 1 (The Tree Evaluation Problem). Let $d, h \geq 2$. An input $I$ to ${\mathit{FT}}_d^h(k)$ encodes the following information:

-

A function $f_i^I:[k]^d \to [k]$ for every internal node $v_i$ of $T_d^h$, and

-

an element of $[k]$ for every leaf of $T_d^h$.

We associate with every node $v_i$ of $T_d^h$ a value $v_i^I$. If $v_i$ is a leaf labeled with the value $a \in [k]$, then $v_i^I = a$. If $v_i$ is an internal node with children $v_{j_1},\dots,v_{j_d}$, then $v_i^I = f_i^I(v_{j_1}^I,\dots,v_{j_d}^I)$. The goal of ${\mathit{FT}}_d^h(k)$ on input $I$ is to compute the value $v_1^I$ of the root.

Figure 1: An illustration of the input to the height-4 TEP ${\mathit{FT}}_2^4(k)$

Figure 1 illustrates the TEP when $d=2$ and $h=4$. There is a straightforward polynomial-time algorithm to compute ${\mathit{FT}}_d^h(k)$, which the reader may verify.

Branching Programs

Branching programs are a model of computation that generalizes decision trees so that the underlying graph is a directed acyclic graph instead of a tree. A branching program contains a finite set of states; for our purposes, these can either query the value of a leaf $v_i$ or a function $f_i(a_1, \dots, a_d)$ for some fixed values $a_1,\dots,a_d \in [k]$, or can be an output state. For every query state $\gamma$, there are $k$ edges from $\gamma$ to other states, for every possible result of the query made by $\gamma$. There is one output state for each value in $[k]$, with no out-edges. Finally, there is a single starting state, with no edges entering that state. Given a BP and an input $I$ to ${\mathit{FT}}_d^h(k)$, the computation $C(I)$ is a path in the graph of the BP, defined as one might expect: Beginning at the start state, we follow the edge corresponding to the result of the current state’s query, continuing until we reach an output state.

For a more precise definition of the computational model, see [2]. For any given degree $d$ and height $h$, we are interested in the size that a BP solving ${\mathit{FT}}_d^h(k)$ must have as $k$ increases.

Restricted Lower Bounds for ${\mathit{FT}}_2^4(k)$

Our main goal is to prove that any BP solving ${\mathit{FT}}_2^4(k)$ must have $\Omega(k^4)$ states. We have managed to prove this under various restricted models. For example, we have the following lower bound:

Theorem 1. Any BP solving ${\mathit{FT}}_2^4(k)$ in which all root queries occur after all other queries have been made has at least $\Omega(k^4)$ states.

Proof sketch. For any computation path, consider the state $\gamma$ making the first root query. Using an adversarial path switching argument, we can show that all inputs whose computations reach $\gamma$ must agree on the values of the children $(v_2, v_3)$. Therefore, we can convert the original BP to one solving the problem ${\mathit{Children}}_2^4(k)$ of computing the pair $(v_2, v_3)$, and apply an already-known $k^4 / 2$ state lower bound for ${\mathit{Children}}_2^4(k)$ from [2].

This approach to proving lower bounds follows a fairly general structure: First, show that a BP solving ${\mathit{FT}}_2^4(k)$ in some restricted model must contain some set of critical states that “know” some information about the input. From there, we can sometimes apply a known lower bound for a related problem, or we may directly argue that only a small fraction of all inputs to ${\mathit{FT}}_2^4(k)$ can reach a critical state, and so the BP must contain a large number of these states. The technical details of these proofs vary depending on the model, and have been omitted. These methods have been successful in proving $\Omega(k^4)$ BP size lower bounds under various restrictions, such as:

-

The root is queried last on any computation.

-

All root queries are thrifty.1

-

The root function is read-once, and the thrifty root query occurs after all non-root queries.

-

The last leaf queried on any computation has not been queried before.

Much of the difficulty in proving BP size lower bounds for general BPs arises when we allow the BP to arbitrarily mix leaf and function queries. One attempt to sidestep this issue involves fixing the internal nodes to be particular functions, such as addition modulo $k$, or various polynomials, and studying BPs that only make leaf queries. It turns out that proving an $\Omega(k^2)$ lower bound for the number of leaf query states needed to solve the height-3 problem ${\mathit{FT}}_2^3(k)$ would imply the desired $\Omega(k^4)$ BP size lower bound for ${\mathit{FT}}_2^4(k)$. This method of examining leaf queries was used by James Cook and Siu Man Chan in [1] to prove an $\Omega(k^h)$ state lower bound for read-once BPs solving ${\mathit{FT}}_2^h(k)$, applying useful properties of certain polynomials over finite fields.

We are hopeful that these results may be extended to prove lower bounds for general branching programs solving the height 4 TEP, and perhaps even the TEP for trees of arbitrary height $h$. Such a result would finally settle the question of whether $L$ equals $P$.

Acknowledgments

I owe great thanks to my supervisors David Liu and Stephen Cook for their helpful guidance and many fruitful discussions throughout the semester.

References

-

S. M. Chan, J. Cook, S. Cook, P. Nguyen, and D. Wehr. New results for tree evaluation. Work inprogress. Dec. 2010.

-

S. Cook, P. McKenzie, D. Wehr, M. Braverman, and R. Santhanam. Pebbles and branching programs for tree evaluation. ACM Trans. Comput. Theory, 3(2):4:1–4:43, Jan. 2012.issn: 1942-3454.doi:10.1145/2077336.2077337.

-

D. Liu. Pebbling arguments for tree evaluation. CoRR, abs/1311.0293, 2013.

Notes

-

A function query $f_i(a, b)$ is thrifty if $(a, b) = (v_{2i}^I, v_{2i+1}^I)$, the correct values of the children of node $i$. ↩